Micromégas by Voltaire

Follow Micromégas, a giant from the constellation of Sirius, as he leaves his home in search of knowledge and stops for a visit on our own planet Earth.

Table of Contents

Chapter One - An Inhabitant of a Planet Orbiting Sirius Travels to Saturn

Chapter Two - A Conversation Between the Inhabitants of Sirius and Saturn

Chapter Three - The Sirian and Saturnian’s Journey

Chapter Four - What Happened to Them on Earth

Chapter Five - The Experiences and Reasonings of the Two Voyagers

Chapter Six - What Happened to Them with Mankind

Chapter Seven - Their Conversation with Mankind

Introduction

What is ‘Micromégas’?

‘Micromégas’ is a pioneering sci-fi novella by Voltaire, portraying a tale of cosmic exploration and philosophical satire. The story follows Micromégas, a giant from a planet orbiting Sirius, and his journey across the universe, culminating in a visit to Earth. Alongside a companion from Saturn, they engage with Earth's inhabitants, exploring themes of knowledge, perception, and the triviality of human affairs from their superior vantage points. This early work of science fiction uses extraterrestrial perspectives to critique and satirise human nature and society, blending imaginative storytelling with philosophical inquiry. Published in 1752, it is one of the earliest examples in the science-fiction genre, and is now presented in a new translation from the original French by Jack Pownall.

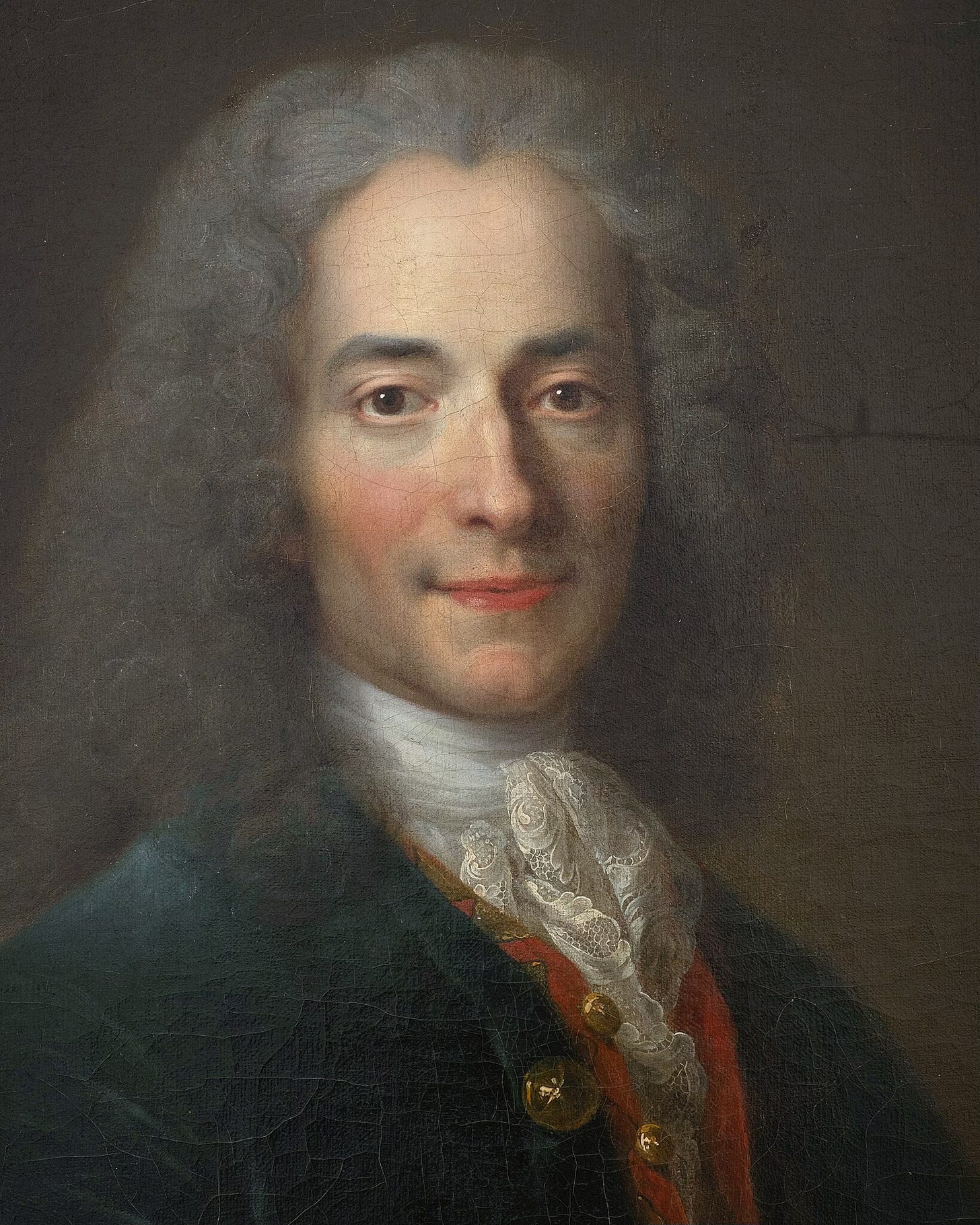

Who is Voltaire?

Born François-Marie Arouet, but better known by his nom de plume, Voltaire was one of the great thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment, with a life filled with more dramatic twists than some of his own works of fiction. Throughout his life, be it through his magnum opus ‘Candide’, his ‘Dictionnaire philosophique’, or myriad other great texts, Voltaire argued for a number of viewpoints that we take for granted today, but which were seen as revolutionary, even heretical, at the time, such as the freedoms of religion and of speech, or the separation of church and state. A dangerous man, then, in the eyes of the French monarchy and the Catholic Church. As a result, the writer, philosopher, and historian was imprisoned in the Bastille, and even exiled to Great Britain.

Unfortunately for his detractors, his exile in Great Britain would do more to inspire Voltaire than to quell him, as he found there a constitutional monarchy that put France’s absolutist regime into a harsh light, and met other great thinkers like Alexander Pope and Isaac Newton.

Returning to France energised and with a widened perspective, Voltaire continued to wield his pen with a vigour that seemed to only grow with the opposition he faced. His experiences in Great Britain had broadened his understanding of political and philosophical ideas, which he then seamlessly wove into his subsequent works. Not only did he champion the causes of freedom of expression and the separation of church and state, but he also became a fervent advocate for civil rights, often criticising the injustice of the French judicial system.

Voltaire's influence extended beyond the realms of philosophy and literature; he engaged in numerous correspondences with European royalty, intellectuals, and fellow writers, spreading his ideas across the continent. His witty, satirical style made his criticisms hard to ignore and even harder to suppress, ensuring his place in the public eye and the annals of history.

Despite facing continual censorship and the threat of arrest, Voltaire's spirit remained unbroken. In his later years, he settled in Ferney, near the French-Swiss border, where he became a figure of enlightenment not only through his writings but also by contributing to the local economy and education system. He transformed Ferney into a model of progress and enlightenment, attracting visitors from across Europe.

In 1778, Voltaire returned to Paris, the city of his birth, to witness the premiere of his latest tragedy, "Irene." The reception was triumphant, a testament to his enduring influence and popularity. Unfortunately, his health was deteriorating, and Voltaire died in Paris on May 30, 1778. His death marked the end of an era, but the beginning of his immortalisation as one of history's most profound thinkers and writers.

Voltaire's legacy is immense, influencing not only the French Revolution but also the development of modern political and philosophical thought. His calls for tolerance, freedom of speech, and separation of church and state resonate even today, making him a perennial figure in the pantheon of great thinkers. Voltaire's life and work continue to inspire those who seek to challenge the status quo, ensuring his place as a luminary of the Age of Enlightenment and beyond.

About this translation

I decided to undertake this new, modernised translation of Voltaire’s ‘Micromégas’ with a view of providing an accessible yet faithful rendering of this early example of the science-fiction canon. When faced with this translation, I felt that the most important thing to get right – apart from ensuring that the philosophical value of the text was kept through the translation – was the challenge of transposing Voltaire’s humorous, sometimes even sardonic voice into English in such a way that it still gets a laugh from a modern reader, while not losing any meaning in the original French.

I would like to think that I have done a fairly good job, but I will admit that the philosopher’s humour has not been 100% translated for fear of transforming the text too much. While the aim was to modernise the text, I would not dare to assume I had either the intellectual force or the right to make any adjustments to the actual content of Voltaire’s writing. As such, all my attempts at modernising this text have been limited solely to its language.

As a fan of Voltaire’s writings, I am providing this translation for free on my Substack, as well as providing an audiobook version of it as a free podcast, in the hopes of introducing new readers to a sensational writer whose innovative thoughts transcend the confines of their original 18th century context, and which still have a lot to teach us nearly 300 years later.

So, sit back, grab a cup of coffee, a mug of tea, or something stronger if you are so inclined, and enjoy this amusing yet philosophical tale of a giant from outer space, a six-thousand-foot-tall dwarf from Saturn, and what they had to teach us minuscule ants on Planet Earth.

Chapter One

An Inhabitant of the Planet Orbiting Sirius Travels to Saturn

On a planet orbiting the star Sirius, there was a wise young man whom I had the honour of meeting during his last trip to our little anthill. His name was Micromégas, a great name for a tall man. He was eight leagues tall, and by eight leagues, I mean, of course, four thousand geometric paces of five feet each.

Some geometers, such useful people to the public as they are, will be rushing to do the sums. So, given that Mr. Micromégas, a citizen of the land of Sirius, measured twenty-four thousand paces, which in turn make one hundred twenty thousand feet, and that we, citizens of the Earth, often measure little more than five feet, and that our globe measures nine thousand leagues in circumference, these geometers, in my opinion, will tell you that the planet that produced Micromégas should measure exactly twenty-one million six hundred thousand times larger than our own little Earth. And there’s nothing more straightforward or ordinary in nature than that. Consider, for instance, the small sovereign states that make up Germany or Italy – which you can wander through in only half an hour – and the Ottoman, Russian or Chinese empires. The chasm in size between them is nothing but a pale imitation of the tremendous differences that nature has endowed upon all beings.

His Excellence being the height that I have noted, the sculptors and painters of our society shall agree without difficulty that his waist should measure fifty thousand feet, giving him very lovely proportions. His nose, being a third of his beautiful face, and his beautiful face being a seventh of his beautiful body, it must be noted that the Sirian’s nose measured six thousand three hundred and thirty-three feet plus a fraction, quod erat demonstrandum.

As for his mind, it was one of our most cultivated. He knew many things and even invented a few. He was but only two hundred and fifty years of age when, while studying, in accordance with custom, at the most celebrated college of his planet, he solved more than fifty of Euclid’s propositions through sheer mental force alone. That’s eighteen more than Blaise Pascal, who, after working out thirty-two by just playing around, according to his sister, became a rather mediocre geometer, and an even worse metaphysician. At around four hundred and fifty years old, on the cusp of adulthood, he dissected many of those little insects that measure no more than a hundred feet, and which eluded ordinary microscopes. From his studies, he wrote a book which, while being rather tantalising, did earn him some trouble. The mufti of his country, a true nitpicker, and ignorant to boot, thought that the propositions in his book were suspicious, improper, foolhardy, and heretical. Suspecting heresy, he pursued him vehemently. The question was whether the substantial form of Sirius fleas was of the same nature as that of snails. Micromégas defended himself with great wit, which earned him favour among the ladies. The trial lasted two hundred and twenty years. In the end, the mufti had the book condemned by jurisconsults who had not read it, and its author was ordered not to show his face at court for eight hundred years.

He was only inadequately upset by being banned from a court filled with nothing but rigmarole and small-mindedness. He wrote a highly amusing song about the mufti, which hardly bothered the latter, then decided to travel from planet to planet to finish developing his mind and his heart, as it’s said. Those of us who merely travel by coach or carriage will doubtlessly be shocked by the equipment they have up there since we — down on our pile of mud — cannot conceive of anything beyond our own customs. Our explorer was marvellously learned in the laws of gravity and all the forces of attraction and repulsion. He made such apt use of them that, whether it be with the help of a ray of sunlight or the convenience of a comet, he could go from globe to globe like a bird flits from branch to branch.

He traversed the Milky Way in little time, and I must confess that, through the stars that litter the galaxy, he never saw that empyrean sky which the illustrious Vicar Derham boasts of having seen at the end of his telescope. I don’t wish to claim that Mr. Derham saw wrongly, God forbid, but Micromégas was there himself, and is a good observer, and I do not wish to contradict anyone.

Micromégas, after a good turn, arrived at the planet Saturn. No matter how accustomed he was to seeing new things, he could not help himself, as he saw the smallness of the planet and its people, from displaying that superior smile that sometimes escapes even the wisest of people. This being as Saturn is no more than nine hundred times bigger than the Earth, and its citizens are mere dwarves, at around six thousand feet tall. At first, he looked down his nose a bit at these people, rather like an Italian musician laughs at Lully when he visits France. But as the Sirian had a good mind, he realised quite quickly that a thinking being may well not be ridiculous merely for being six thousand feet tall. While he amazed them at first, he soon became friendly with the Saturnians. He struck up a close friendship with the secretary of the Saturn Academy, a man with a lot of wit who, if truth be told, had not invented anything, but who could speak very well of others’ inventions and who could write some short verses and long calculations reasonably well. I shall quote here, for the satisfaction of my readers, a peculiar conversation that Micromégas and the secretary had one day.

Chapter Two

A Conversation Between the Inhabitants of Sirius and Saturn

His Excellency had laid down, and the secretary brought his face close to the other's.

‘We must admit,’ said Micromégas, ‘that nature is quite varied.’

‘Yes,’ said the Saturnian, ‘Nature is like a flowerbed whose flowers...’

‘Oh!’ replied the other. ‘Let's leave the flowerbed where it is.’

‘Nature is,’ continued the secretary, ‘like a group of blondes and brunettes whose finery...’

‘Oh, what do I care for your brunettes?’ said the other.

‘Okay then, nature is like a gallery of paintings whose brushstrokes...’

‘Oh no!’ said the explorer. ‘I’ll say it again; nature is like nature. Why look for comparisons?’

‘To please you.’

‘I do not want to be pleased. I want to be instructed. Start by telling me how many senses the men of your globe have.’

‘We have seventy-two," said the academic. ‘And each day we complain of having so little. Our imagination goes further than our needs. We find that with our seventy-two senses, our planet’s ring, and our five moons, we are too limited, and despite our curiosity and great number of passions which we owe to our seventy-two senses, we can still find time to be bored.’

‘I’ve no trouble believing it,’ said Micromégas. ‘Since on our planet we have nearly a thousand senses, and we still have some vague yearning, some concern, that never ceases to remind us that we are mere small things and that there are much more perfect beings. I have travelled a bit. I’ve seen mortals so very below us, and I’ve seen some that are so very superior, but not even one that did not have more desires than real needs, and more needs than satisfaction. One day, I might find the land where we want for nothing, but until now I have heard no good news of such a land.’ The Saturnian and the Sirian then ran dry of speculation, but after much ingenious and uncertain reasoning, they needed to get back to the facts.

‘How long do your people live?’ asked the Sirian.

‘Oh, very little!’ replied the small man from Saturn.

"Exactly like us," said the Sirian, ‘We’re always complaining about how little we live. It must be a universal law of nature.’

‘Alas!’ said the Saturnian. ‘We live but five hundred great revolutions of the sun.’ (Fifteen thousand years, by our way of counting). ‘You'll agree that it is almost as if we die the moment we are born. Our existence is but a point, our duration an instant, our globe an atom. Scarcely do we begin to learn a bit and have some experience before death comes. Personally, I daren’t make any plans, feeling as I do like a waterdrop in an immense ocean. I am ashamed, especially in front of you, of how ridiculous I feel in this world.’

‘If you weren’t a philosopher,’ replied Micromégas. ‘I’d fear that you would be pained to know that our lives last seven hundred times longer than yours, but you know too well that when the time comes to return your body to the elements and reinvigorate nature under a different form – in other words, when you die – whether this moment of metamorphosis comes after living for an eternity or for a day, it’s precisely the same. I have been to lands where people live a thousand times longer than in my own and found that they still find reason to complain. Yet there are people everywhere with the common sense to come to terms with things and thank nature's creator. Across this universe, he has strewed an abundance of variety with some kind of admirable uniformity. For example, all thinking beings are different, and all are basically alike in the gift of thought and desire. Matter is spread out everywhere but has diverse properties on each planet. How many of these diverse properties do you have in your matter?’

‘If you mean those properties without which we believe that this globe could not endure as it is,’ said the Saturnian. ‘Then we count three hundred, such as extent, impenetrability, movability, gravitation, divisibility, and the rest."

‘Apparently,’ replied the explorer. ‘This small number is sufficient for the Creator's view of your little dwelling. I admire his wisdom completely. Everywhere, I see differences, but also proportions. Your planet is small, and so are its people; you have few sensations, and your matter has few properties. All that is the work of divine providence. You've examined it well – what colour is your sun?’

‘A very yellowish white,’ said the Saturnian. ‘And when we divide one of its rays, we find it contains seven colours.’

‘Our sun verges on red,’ said the Sirian. ‘And we have twenty-nine primary colours. There is not a single sun, amongst all those that I have visited, which resembles another, just as on your planet there is not a single face that isn’t different from all the others.’

After several questions like this, he inquired about how many essentially different substances there were on Saturn. He learned that there were only around thirty, including God, space, matter, extended beings with senses, extended beings with senses and thought, thinking beings with no extension at all, those who were self-aware, those who were not self-aware at all, and the rest. The Sirian, with the three hundred of his own land, and the three thousand others he had discovered through his travels, was stupendously shocked by Saturn’s philosophy. In the end, after exchanging with each other a bit of what they knew and a lot of what they didn’t, and after reflecting for an entire revolution of the sun, they decided to go on a little philosophical journey together.